Alex Westfall

Community update with Alex Westfall

In 2014 we met Alex as a student during our summer program Art on the Farm. Two years later she returned to participate in our photography residency How to Flatten a Mountain. In the years since, she has completed her undergraduate studies, earning a BA in Modern Culture and Media from Brown University in 2020. Alex makes films and photographs and she writes about music and film. She has contributed to several online publications including Pitchfork, VICE Asia and Rookie among others. She spends her time between the Philippines and Los Angeles. We were so glad to recently re-connect with Alex during on of our information sessions for Art on the Farm and curious to learn a little more about her practice and what’s been occupying her time since she was last on the farm.

CHS: You make photographs and short films. How do your working methods differ for these two mediums? In what ways might your approach be similar?

AW: I love both mediums equally, and I definitely see a through-line! I made my first darkroom print when I was 13—long before I started work in time-based media. I think it’s nice to approach filmmaking from a photography perspective—I’m extra conscious of the message or emotion conveyed by an image. For a lot of my film work, I shoot 16mm film on a Bolex camera. In many ways, the process is just like using a 35mm camera for stills—it’s you and the lens. You’re forced to slow down, take a light reading, and compose through a viewfinder.

I’m interested in breaking down the barriers between fact and fiction; between narrative and documentary. In my photographs, I like to blending my experience moving through the world with dreamlike or unworldly moments—in a way, exploring what place means. In my film work, I’m interested in imbuing imagination into the historical archive—in another way, exploring my understanding of time. To me, the most significant difference is temporal…in film, the ability to cut and paste shots so that meaning emerges from their juxtaposition.

Of course, when it comes to certain film projects, there are so many layers of collaboration involved. But for me, directing an actor for a narrative scene doesn’t feel too different from directing my sister for a ‘casual’ photograph. I think that’s something so wonderful about working behind the lens–the people in front of it can complete the image for you, whether they’re acting or being themselves.

CHS: You participated in our summer program Art on the Farm, 2014 and returned for our residency How to Flatten a Mountain, 2016. What are some of your memories from your time on the farm? How did these experiences help shape your creative practice?

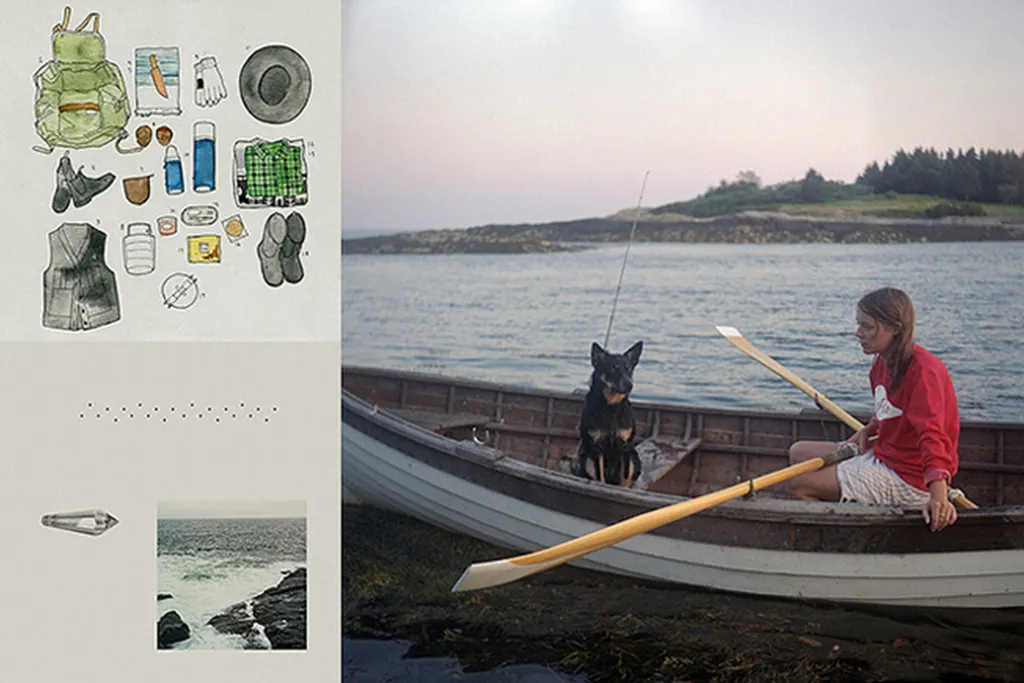

AW: Art on the Farm was when I began to find my voice in image-making; where I learned to think seriously about the act of looking, to sequence images, to make presentable prints (thank you, Frank!). The afternoons in the darkroom were pure magic. I’d emerge from there into the pastoral landscape, and thought about nothing but creation throughout the three weeks. It was the same with How to Flatten a Mountain—a week and a half with the seemingly infinite time and space to imagine.

I always come back to this story, but during my summer on the farm, it was a goal of mine to make portraits of strangers. I was so nervous to approach people I didn’t know…so as an exercise, Frank would ask me to walk the path around Ballybawn and photograph every person I’d come across. Given the rural setting, I’d meet maybe two or three people on the miles-long trek. When I’d return to the studio, Frank would have me do the walk again. And then again, and then again! By the end of the summer, I had an immense amount of experience socializing with strangers for the sake of a photograph that my nerves disappeared… and they’re still gone to this day. This was just one of the reasons I came out of both Art on the Farm and How to Flatten a Mountain with so much work—many images I still have in my portfolio today.

My time on the farm also showed me how important it is to make work in community…I still remember so many meaningful crits, unbelievable meals, expeditions around the woods, tea-stained all-nighters at the barn… gosh, I dream of returning as soon as I can!

CHS: In addition to your work with lens-based mediums, you often write about film and music. What do you learn when writing about someone else’s work? How do your experiences as a creative professional inform how you think and write about other people’s work?

AW: I consider writing about the work of others as an act of love. It allows me to honor people who in my eyes are making wondrous contributions to the world. It gives me a chance to study their work with great care, which leads to the richest conversations. For instance, when I had the chance to speak with the filmmaker Garrett Bradley, a seconds-long sound I noticed in her film Time gave way to an illuminating censure about how for her, documentary filmmaking reflects the totality of what it means to be alive. I doubt I would’ve picked up on that brief sonic moment if I didn’t understand how to manipulate sound in editing software.

I prefer the interview as a writing form (as opposed to a review or a critique) because it gives space to the artist to speak on their work and process on their own terms. To that end, it’s important to me to highlight femme-identifying artists of color. I don’t consider writing to be a native skill—expressing something visually comes most naturally to me. I like the challenge of articulating what it is that moves me about someone else’s work. I also adore the act of listening—it’s so energizing to hear about what compels someone to make something.

CHS: I know you’re a big music fan. What are you listening to right now?

AW: I am loving Norma Tanega’s album from 1971, I Don’t Think It Would Hurt If You Smile. She is a Filipina-Panamanian-American songwriter who defies genre, but you can hear her influences in a ton of contemporary pop and folk tracks. She wrote songs for Dusty Springfield, too. When you think of experimental music in the 70s, you mostly think of white guys jamming with an analog synth or something, but Norma was literally constructing and playing her own instruments out of ceramic earthenware at the same time! Lately, I have also been listening to soundtracks, especially from movies I haven’t seen. I like to imagine my own images as I listen. One of my current favorites is this one from Wong Kar-Wai’s Ashes of Time, “Jingzhe“… so aching and beautiful.

CHS: We’ve all been spending a lot of time at home lately. Have you been able to make new work? Are there projects you have underway? What are some challenges you’ve faced working from home and having limited movement?

AW: It’s been so difficult! There was a three-week period last year where all I could bring myself to do was chop vegetables—I was so numb, emotionally and creatively. The art-making process can be so isolating, and it’s easy to lose faith in your creative practice when the world is coming apart. For me, it’s been key to cultivate proximity (even if from a distance) during this time. I love long phone calls about ideas, and every day I am in some sort of creative dialogue with friends who are directing plays, studying law, programing computers. It’s such a gift to hear about my projects through the lens of other disciplines, and I get so much energy from every correspondence. I’m also about to start as a mentor at Las Fotos Project, an after-school photography program for teenagers. I can’t wait for the community that the experience will bring.

It’s happening slowly, but I’ve been working on a project that explicitly blends my love for photography and film. It’s an experimental documentary that imagines the life of the photographer Francesca Woodman as a high school student. We share the same school, and I’ve spent the last few months collecting oral histories from her friends, housemates, teachers, and family members. So much of the discussion around Francesca’s life is eclipsed by the tragic pieces of her biography, and her work has been subject to overinterpretation and intellectualization by (mostly male) critics who didn’t know her. I’m excited to embark on a depiction of her story that subverts this narrative; one that celebrates her as someone in formation, both as an artist and a girl.