Alexandra Huddleston

Alexandra Huddleston participated in our 2016 artist residency for photographers How to Flatten a Mountain. Born in Freetown, Sierra Leone and raised in Bethesda, Maryland, USA, and Bamako, Mali, her upbringing has led her to explore landscape and culture from an international and interdisciplinary perspective. In 2007, she won a Fulbright Grant to research and photograph traditional Islamic scholarship in Timbuktu, Mali.

Alexandra is a photographer, writer, and walking artist. Her most recent projects describe landscape as a space of dynamic change. It’s a vision gained by walking thousands of miles in the last two decades. At the center of her work is the question: how does walking influence our perception and depiction of space and place? Alexandra presents her work to the public through her books, exhibitions, and lectures.

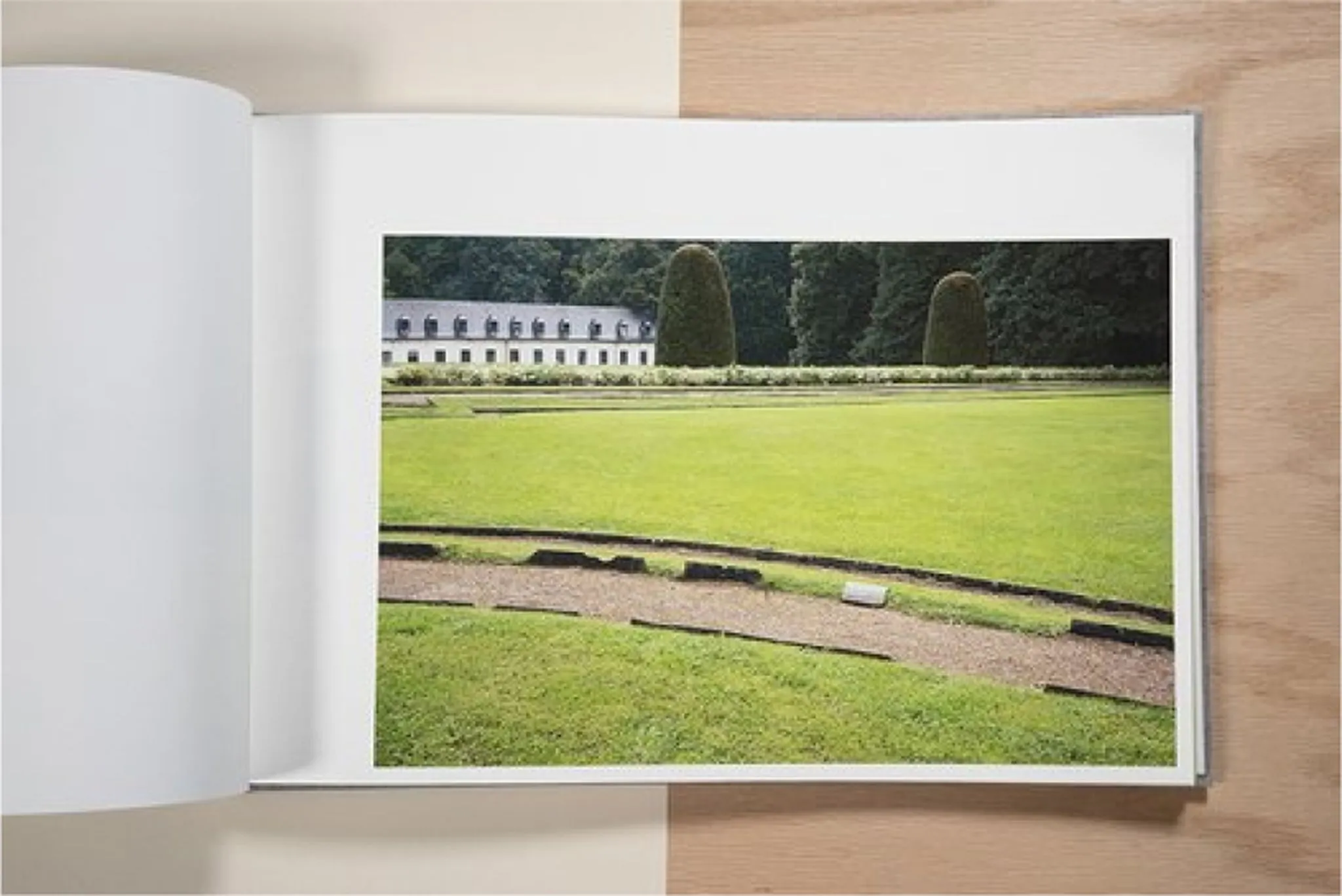

Alexandra recently published Traces of Time, a hand-bound, limited edition artist’s book. Centered around eight photographic sequences, interspersed with large, single images, the book explores how walking – in particular walking in a park – influences our perception of space and place. Through a close, meditative, and pedestrian observation of the built and biotic landscape of one of Brussels’ most beloved parks – the Jardins de l’Abbaye de la Cambre – this work highlights the small, almost imperceptible, hourly and daily transformations that mark time’s passing.

alexandrahuddleston.com

@adh2103

CH You’ve recently completed Traces of Time, a handmade book of photographs from your time at the Boghossian Foundation – Villa Empain in Brussels. Can you explain how this project evolved from your initial ideas to its completed form? How closely does the book adhere to your initial proposal for the residency?

AH In general, the work I pursue tends to closely follow my initial ideas for a residency, but that was not the case for this project because the pandemic delayed my travel to Brussels. When I finally arrived at the Villa Empain in August of 2021, my initial ideas for the residency felt irrelevant to how my work had developed in the interim two years!

However, once I had decided to use my time at the residency to walk and photograph the Jardins de l’Abbaye de la Cambre (one of Brussels’ most beloved parks), I knew that I wanted to photograph the space in such a way that some of the final works would involve sequences or arrays of multiple photographs. I also knew that changes in time and motion were likely to be key. That said, I don’t like to be too prescriptive with my work. While photographing, I believe in allowing the space and the landscape itself to influence me. When in the studio, I listen to what the photographs are telling me, rather than imposing my preconceptions on them.

I still think it’s ironic that “time” became the focus of this work because initially I wasn’t sure there would be enough changes to document! Summer is a fairly static season compared to spring or fall. However, in the end, it was those very small, inconsequential changes that fascinated me: a can left on a wall and then cleaned up, a small change in light, flowers slowly wilting…

CH Walking, or rather, what you learn by walking, is central to your creative process. How do you balance this immersive act with the desire to document your experience through photography? Has your understanding of when to stop and make an image evolved as you continue to work in this way?

AH I always find this question curious because I’ve never felt that there was any tension between my photography and my immersion in the landscape. I was asked this often by fellow pilgrims during the three walking pilgrimages that I’ve completed. On each journey I met pilgrims who had deliberately left their camera at home so they could be more immersed or ‘at one’ with the experience.

When I have my camera with me, I notice more! I slow down and pay more attention to the landscape. Without the camera I let the walking become a sport. It’s true that I become immersed in my speed and my ability to cover extreme distances, but I’m much less immersed in my actual surroundings. This feeling has been tested. On my last pilgrimage, my camera broke for a few days, but I didn’t become more immersed in anything. Instead, I made good time, and I was grumpy!

Over time I’ve learned not to think too deeply about my impulse to stop and take a photograph. I try to put aside any preconceived judgement about what is ‘worth’ photographing and instead go with my impulse. Some of my best photographs are of inconsequential things, a bit of grass or a curious curve in a hill. I never would have stopped to take those photographs if I was listening to my brain. I photograph a lot and leave the thinking for later, when I edit the work. I should add that although I use a digital camera, I always look through the viewfinder to make the photographs, and I never review my work on the camera’s back monitor.

CH Your work takes shape on trips away from your home. Is encountering new places essential in your process of engaging the landscape?

AH My answer is yes and no. Encountering new places is not essential. I’m currently editing a series that I photographed over three years within two kilometers of my home.

However, yes, encountering new places is essential to developing a wider and more comprehensive understanding of how different landscapes and different ways of walking lead to different ways of feeling, understanding, and representing space. My book “Traces of Time” is composed of eight, linear photographic sequences interspersed with large, single images. The linear flow of both the book design and the sequences was a considered decision. The Jardins de l’Abbaye de la Cambre (The Gardens of La Cambre Abbey) are dominated by several manicured gardens with long, straight paths, straight lines of trees, straight flower beds, and geometric topiaries. The quality of its landscaping deeply influenced my photography. I know this because I’ve worked in a wide variety of places, and I’ve watched as other types of spaces have led to very different types of photographic work.

Ireland, in particular, has taught me a relational way of understanding landscape. Every hill and rock exist in relation to their surroundings: hills, rocks, stars, rivers, ice cream parlors, and gas stations. It was exploring the Neolithic sites in counties Sligo and Kerry that led to that particular revelation.

Lastly, I should add that I don’t really have a ‘home’ landscape. I was born in Africa, and grew up within different countries, culture, and landscapes. My parents are American and I’m a US citizen, but I’m not ‘native’ to anyplace. I sometimes think that walking a place is my way to break that barrier of ‘not belonging’ and to allow myself to make a landscape my own.

CH Handmade books house many of your recent projects. How does this format inform the way a viewer experiences your work? Can you tell us about Kyoudai Press, its ethos, and development?

AH Making a handmade book allows me to be picky and particular in my design decisions! I can customize everything: the paper type, the printing, the color of my end sheets, binding thread, and book cloth. Handmaking books has given me a visceral understanding of the mechanics of book design. I use the word ‘mechanics’ on purpose because, fundamentally, a book is an ancient type of machine for delivering meaning. Through experience I’ve learned how to customize and control that machine. In particular, I’ve learned that a more complicated design is often not a better design! “Traces of Time” went through four major design revisions. My early drafts included fold-out pages for the sequences. Eventually, I realized that the fold-out pages confused the reader and distracted from the flow of the story.

The Kyoudai Press was begun when my brother and I decided to collaborate on a book of photography and poetry – my brother, Robert, is the poet. Japanese art, poetry, and thought has deeply influenced my work. I studied abroad in Kyoto during university, and my second walking pilgrimage was around the island of Shikoku. These experiences inspired me to choose the name the Kyoudai Press – ‘kyoudai’ means ‘sibling’ in Japanese. Since then, the press has become more my project than my brother’s but collaboration has remained a central ethos, as has the influence of Japan. It’s no coincidence that the type of binding used in “Traces of Time” is a Japanese stab binding!

CH You attended our first iteration of How to Flatten a Mountain, a residency for artists working in photography. What do you recall from this experience? How has it informed your artistic practice?

AH The simplest answer is that How to Flatten a Mountain brought me to Ireland. Since then, I’ve been on two other artist residencies in Ireland and walking its landscape has had a profound influence on my photography and my understanding of land and space. Each time I return to Ireland I seem to have another breakthrough in my work. Cow House Studios was at the start of it all!

In the five years before the Cow House Studios residency I had been working too long in isolation. I had largely forgotten the joy and the inspiration that comes from being in conversation with other artists. In contrast, the group activities, the animated conversations during mealtime, and the large, shared studio space made How to Flatten a Mountain a collaborative and convivial experience.

The residency brought together a group of dynamic photographers who took landscape seriously as their artistic focus and as a space of conceptual, aesthetic, and cultural meanings. While that might seem obvious now, it was much less obvious to me in 2016. Being in this dynamic environment gave me confidence in the importance and scope of landscape photography.

Perhaps what I learned most deeply during the residency was that my experience of Ireland had little to do with the view presented through mass tourism. As long as I ignored the stereotypes and looked clearly at what was before my eyes, I saw a culture and a landscape that were as unique and as foreign in their own way as Mali or Sierra Leone in West Africa where I had grown up. Both no place and every place are ‘exotic,’ and the most astonishing sights often occur where everyone else has looked, but not seen them.