SV Randall

SV Randall was one of five artists invited to participate in our 2016 autumn artist residency, The Centre for Dying on Stage. He is an interdisciplinary artist working with sculpture, photography and installation to examine the relationship between consumer, commodity, and transformation. His artist statement asserts that “Within a culture of feverish consumption and retinal impatience I often make ‘fast’ objects by the slowest means possible.”

Among many accomplishments, SV is the recipient of the Toby Devin Lewis Fellowship Award, a Sculpture Fellowship through the Virginia Commission for the Arts, and a Visiting Artist Grant through the Institute for Electronic Arts. He recently received his MFA in Sculpture + Extended Media from Virginia Commonwealth University and currently lives in New Mexico where he is teaching in the MFA program at NMSU and the BFA program at UTEP. SV has generously taken the time to answer a few of our questions and we’re grateful for his thoughtful and informative responses.

CHS: You participated in our 2016 residency The Centre for Dying on Stage which in its effort to explore the overlap between performance and performativity took a highly collaborative approach to producing a “play” as its culmination in Wexford Arts Centre’s Theatre. How did you find the collaborative process? Did the residency provide an opportunity to approach your own practice from a new perspective? What were the challenges working in new mediums and presentation methods?

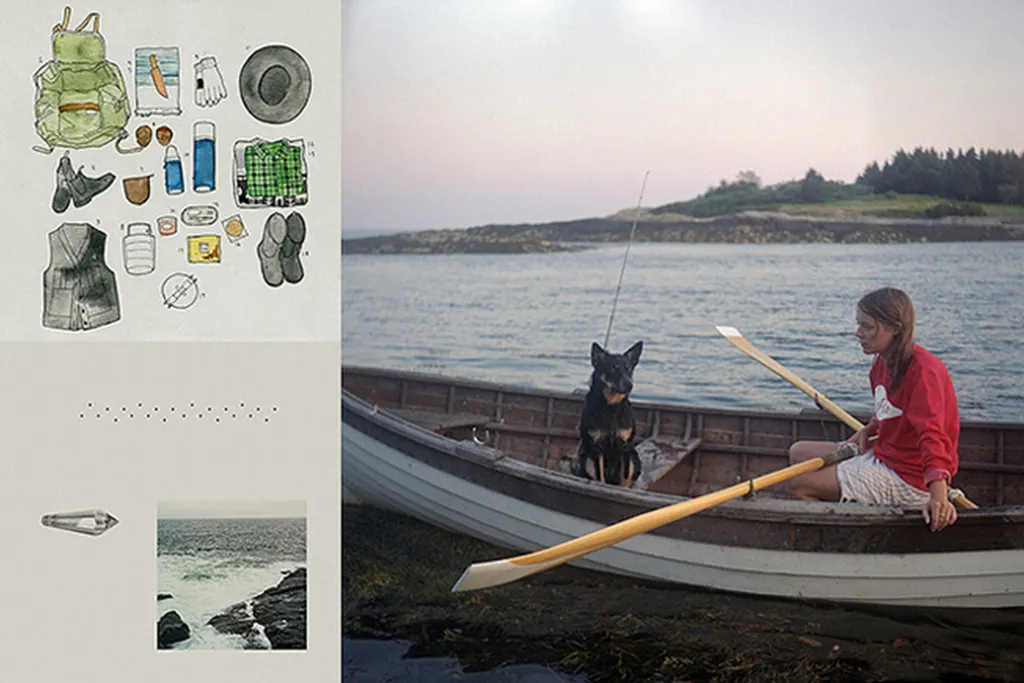

SV: The Centre for Dying on Stage was such a unique project that I’m so grateful to have been a part of. For me – art is often a solitary process within the confines of a studio. This residency definitely offered a new way to think about my process. It brought together five very different international artists to co-create an exhibition in the form of performance under the guidance of curator Kate Strain. We lived, cooked, exercised, thought, and performed together. Some of our early challenges were finding ideas that resonated with each of us; ideas that everyone felt could fit within their independent practice while still converging in an overlapped interest for everyone in the group. The final performance became the embodiment of our developing ideas and highlighted this layering of our shared interests. Supplement to the performance we created: a printed newspaper that we collaboratively designed, a projected video, and an original score composed by a sound designer back in the states. The performance became a means to laminate these different modes of thinking and making into a kind of stratified constellation of ideas.

CHS: You have been on several residencies since obtaining your MFA. How have these experiences facilitated your transition to making work outside of an academic setting? How do you feel residencies, in general, have helped advance your practice?

SV: I’ve been fortunate to have participated in a number of residencies since completing graduate school at VCU. Residencies have acted as a means for me to sustain my studio practice full time while affording me the time and space to experiment and continue asking the questions I want to guide my work. I took four years off between my BFA and MFA so that I could save up money and get some experience outside of academia. When I made the choice to get my MFA, my life hinged around a rigorous engagement with art 24-7. Twelve hour days in the studio every day of the week, artist lectures, weekly studio visits, curated readings, critiques, exhibitions, and ongoing discussions with my colleagues and faculty. To go from such an intensive art-centred reality to a day job right away would have put my practice in a damaging shock. So I applied to residencies as a way to keep that momentum going and transition out of school as smoothly as possible. These residencies have not only allowed me the time to continue working in the studio but they’ve also offered the chance for me to reflect on my graduate school experience while working to articulate some of the ideas and projects that I started as a student.

CHS: You are spending some time this year teaching at both University of Texas, El Paso and New Mexico State University. Have you enjoyed teaching? What are some of the challenges you faced in working with students? Is it something you would like to pursue further?

SV: Yes – I’ve been invited to teach at NMSU and UTEP this year where I’m working with a wide range of students across an array of classes spanning Introductory, Intermediate, and Advanced Sculpture to MFA Critique and Seminar. So far I’ve really enjoyed my time teaching in these BFA and MFA programs and it’s been an amazing experience to work with so many curious minds and young artists with such unique approaches to making art. Working with the MFA students here keeps me involved in a dialogue that resembles one of my MFA cohort, which I am able to approach through a different lens. Through all of my classes, the exchange of ideas is reinvigorating and inevitably allows me to reflect on my own studio practice. As a visiting faculty member commuting between these two states – I’ve been keeping really busy! The biggest challenge I’ve had thus far has been finding the time to dedicate to all my new ideas within my studio practice.

CHS: In part, your practice investigates how sculpture and installation have the potential to explore narrative. During your residency at Cow House, you spent a great deal of time working with video. How did you find working with such a linear medium? Did you feel the need to impede video’s tendency to imply relationships between sequential shots? Have you continued to work with video since your time in Ireland?

SV: I came to Ireland with a video camera and a field recorder. It felt like such an exciting challenge to move completely out of my comfort zone and to take on such an ambitious project as a total novice within the medium. Needless to say, the learning curve was steep. I would spend the mornings watching tutorials on colour grading and trying to better understand editing software, during the day we would shoot, and in the evenings I would edit. Although most of my sculptures centre around the concept of time – namely how objects can transform in significance as well as appearance over time – the sense of time in video is of course, entirely different. We would often piece together shots we wanted without really knowing how those shots would work in relationship to one another through the linear sequencing of time in video. The final video we created implies a linear narrative but bypasses any real plot or logical structure. For the performance we wanted the video to evoke certain cinematic expectations within the viewer. The performance actually started off as a projected video in this traditional theatre space. Kate introduced the project, the lights dim, and the video began with these rolling, dramatic landscape shots – real moody. And just a few minutes in, the video glitches and “malfunctions” and then the performance began much to the confusion of the viewer who has just been swept up into what seemed like a full-length feature film. I haven’t worked with video much since my time in Ireland but I’m working on a new project which will revolve around gestures and performances recorded through optics. Video will be an important instrument to this new body of work and it’s a medium that I’m excited to re-integrate into my practice.

CHS: What have you been working on most recently? Can you describe a bit about your creative process and the themes you’ve been exploring?

SV: My creative process seems to constantly evolve and shift. I was initially trained as a painter but ended up studying sculpture in graduate school. Many of my earlier works started with an idea for an object which I would fabricate in the studio. The process left me feeling dissatisfied and the resulting work felt static for me – it felt too calculated. Lately, I’ve been allowing curiosity to become the driving force in my practice. Rather than making work that casts statements, I’m interested in work that poses questions. I like to start with topics of research that I can link to other fields. I love spending countless hours researching certain topics from different perspectives. With many of these larger projects, I rarely have an imagined idea for how the work will materialize, instead, I want to allow more openings for active inquiry, studio research, and experimentation. My experience at Cow House really changed how I think about my work and helped facilitate this shift toward layered inquiry.

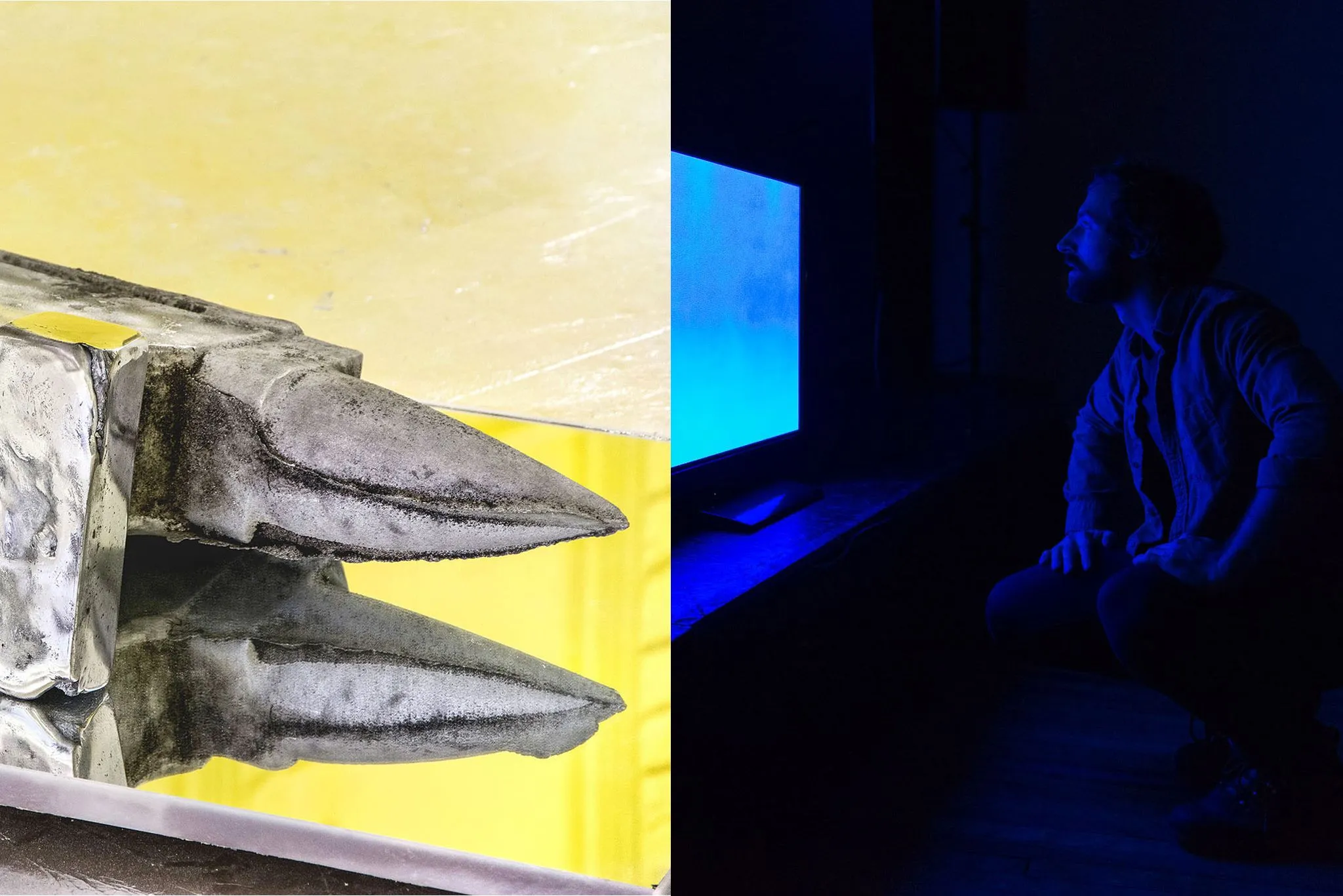

I’m embarking on a large thematic project this year. Everything is still fairly early in the planning phase. I see this project as a body of work spanning writings, drawings, photographs, video, and performance centring around the idea of “the mirage”. The mirage, of course, is an optical illusion which only comes to exist under certain environmental circumstances (warm sunny day, absorbent ground, and a certain vantage point from the viewer). When the conditions are just right, light bends and distorts as it is seen resulting in a mirrored illusion often perceived as water. I’m interested in the mirage as a taunting illusion. It takes the form of something which does not exist in an environment when the viewer might need it most. The mirage cannot be obtained, it can not offer sustenance in the form of water, and it can not be touched. I wonder if I can link this ancient phenomenon to something ubiquitous in our current time frame. I’m working to form a connection between the mirage and concepts of “the virtual”. Both are immaterial, unknowable, and beyond our ability to touch. I think this body of work will engage heavily with optics as both a visual means to perceive the world and a self-reflexive device of how we’ve grown to live more in screen space.